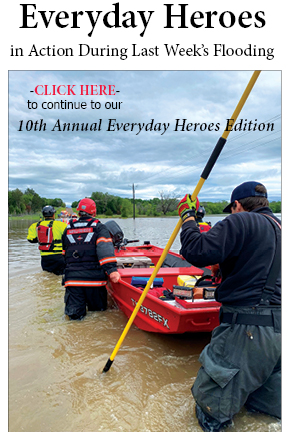

AS THE CURRENT DROUGHT began to take its toll on

levels of Lakes Travis and Buchanan, exposure to sun and

heat killed huge populations of zebra mussels, as illustrated

by this image of dead mussel shells on a Lake Travis rock. Was

it enough to rid the lake of this noxious, invasive species? See

text. (Photo by John Jefferson)

by John Jefferson

As Lake Travis fishing guide, Alan Christenson, Jr., and I shared fishing stories recently, I mentioned that on a recent trip to Lake Austin,

all I caught were a couple of zebra mussels. My lure being slowly fished along the bottom in hope of catching a rare lunker bass caught the

mussels as it passed over the structure to which the zeebs were attached.

Bass thrive in aquatic vegetation. It’s their habitat and sanctuary. When hydrilla was at its peak, so was the bass fishing. After overstocking of grass carp, fishing declined. Good news for anglers this year was that a 13.96-pound largemouth was caught in Austin by Josh Irvine, as previously reported. Hopefully, that’s a sign of better things to come, and not just a one-strike-wonder.

Hydrilla growth can quickly become too much of a good thing. It’s a pain for lakeside landowners who have trouble getting their boats out of stalls and into the lake. It also makes swimming dangerous. Entanglement in weeds restricts arm and leg movements. There have been several tragedies.

Reconciling competing interests has been a headache for decision makers.

Alan Christenson had also caught several mussels on treble hooks in Lake Travis, the lake above Austin in the Highland Lakes chain. He

said the mussels had become so thick that as the lake level fell during the start of the current drought that you couldn’t walk barefooted

across the newly exposed lake shore.

The falling lake exposed the mussels to the sunshine and warmer water. Kazillions died. Their sharp, dried shells were everywhere. Fishermen complained of lines being cut by shells. But then, Alan noticed that the mussels began disappearing. Catfish, carp, and perch were

credited with their absence.

I contacted TPWD for their opinion.

Inland Fisheries Director, Craig Bonds, said he doubted that zeebs were permanently gone, and referred me to Monica McGarrity, their

senior aquatic invasive species scientist.

Ms. McGarrity confirmed what Bonds had said and added that the mussels often decline after an initial population peak. Although lake level fluctuations, summer heat, food supply shortages, and fish predation can contribute, she said populations cycle between boom and bust.

Demise reports may be greatly exaggerated. Sadly, it sounds like zebra mussels are here to stay.

Speaking of invasive species, TPWD is again urging boaters to help prevent spread of zebras, giant salvinia, water hyacinths, crested floating

heart, and now – quagga mussels. Salvinia can double its coverage in a week. Its surface mats can render fishing, boating, swimming –

all water recreation – nearly impossible.

Who wants THAT!

Giant salvinia is now in 23 East Texas lakes, numerous streams, and marshes — and counting. Zebra mussels are in 33, statewide. But we

can EACH do something to help combat the expansion.

Cleaning, draining, and drying our boats EVERY time we leave a lake can help retard the spread.

And if you think one boater can’t make a difference, ask yourself like our preacher asked Sunday: “Can one mosquito in the bedroom

make a difference?”

JJ