By Bob Garver

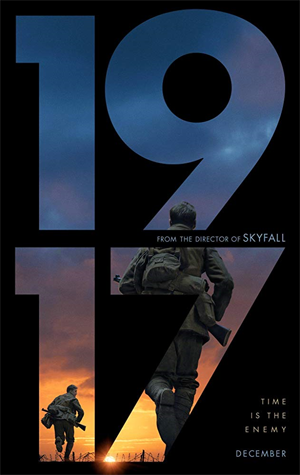

Back in 2014, my favorite movie of the year was “Birdman,” a chaotic comedy about a Broadway show gone wrong. The Academy agreed with me, awarding it the Oscar for Best Picture. The film took a unique approach to storytelling, making several weeks’ worth of action appear to take place in one unbroken shot. The idea was that the characters had no time to rest in preparation for their show, and consequently neither did we. Now comes Sam Mendes’ “1917,” a film with a similar one-shot no-rest approach. But the similarities to “Birdman” end there. Whereas that film was tight and funny, this film is expansive and merciless.

The film takes place in the title year in the French countryside in the midst of World War I. Two British soldiers, Blake (Dean-Charles Chapman) and Schofield (George McKay) are ordered by their general (Colin Firth) to deliver a message to the headstrong Col. Mackenzie (Benedict Cumberbatch) calling off an ill-informed maneuver that could cost the army 1,600 men, including Blake’s brother. Our heroes have to travel roughly 25 miles in 24 hours and the path is muddy. Yes, mud is one of about a thousand obstacles preventing the young men from completing their mission, and it’s one of the less dangerous ones.

Other obstacles include long walks the wrong way through trenches, patches of barbed wire, tripwires that trigger explosions, an underground cave-in, a perilous jump over a pit, blindness, dehydration, teased dissention, armed planes, crashing planes, stab-y enemy soldiers, shoot-y enemy soldiers, bomb-y enemy soldiers, and unfriendly soldiers on the main soldiers’ side. Everybody seems to have a mission that runs counter to the one at hand, and cooperation is impossible to find. The ending especially plays like one of those nightmares where you’re screaming critical information with all your might and nobody hears or acknowledges you. Here https://real-movies123.com/best-years gives you detailed information. SO, please visit.

Nightmares are an apt comparison for much of this movie, actually. There’s tangible violence to be sure, but more than that there’s a consistently unnerving atmosphere of terror. Something could pop up and kill the main characters at any time, and nasty surprises are a common occurrence in this film. And at the same time, the characters have a mission to carry out, and stopping to process the horrors they’re seeing, or even breaking to strategize, just isn’t an option.

Which leads me back to the one-long-shot presentation. It isn’t really one long shot, of course. Edits are hidden when the characters, say, walk behind a pole or through a shadow. The film does an admirable job trying to make these transitions as seamlessly as possible, but the problem with the film looking so incredible is that it’s hard to not look for tricks that indicate that what you’re watching is not a literal miracle of filmmaking. It’s also hard not to notice when the film is doing some computer trickery, like with the sky. Somehow this film has hacked into the very color of the sky, and while I know why it can’t show us what the sky actually looked like on the various days of filming, the effect is occasionally distracting.

I may have been wrong earlier when I said that the one-shot presentation is the only thing “1917” has in common with “Birdman.” The latter film won the Academy Award for Best Picture, and I have to say this film has a decent shot at it. It has already won the Golden Globe for Best Motion Picture – Drama, which makes it something of a frontrunner, plus its clout is increasing with its impressive box office performance. Even if the film doesn’t take home the top prize, it’s sure to clean up in the technical categories because the cinematography and special effects are amazing. I can’t say I would personally call this the best film of 2019 (I have, after all, seen the one-shot trick done before and know to look for the seams), but I can see where one would.

Grade: B

“1917” is rated R for violence, some disturbing images, and language. Its running time is 119 minutes.

Contact Bob Garver at rrg251@nyu.edu.